Last updated on October 8, 2024

4 of the Most Common Dangerous Weeds for Horses- and How to Avoid Them

If you’ve ever searched “dangerous weeds for horses” the results can be terrifying! There are dozens of native and invasive weeds, shrubs, and even trees that can cause health issues for horses ranging from mild to deadly. Some of them are widespread across the country, and some of them are secluded to certain climates or habitats. While horses don’t typically seek out and graze on plants that are hazardous to them, it is important to be aware of the dangerous plants that can be lurking in your pastures or hay bales. So, we’ve combed the scary articles on the internet and gathered information about some of the more common poisonous weeds that could potentially be a serious threat. Not to scare you, but to educate you on what to look out for so you can avoid a catastrophe.

It’s important to note that we purposefully did not include shrubs or trees, just grasses, weeds, and flowers that typically grow wild in or around pastures and agricultural land.

4 Dangerous Weeds to Look Out For in Your Pasture

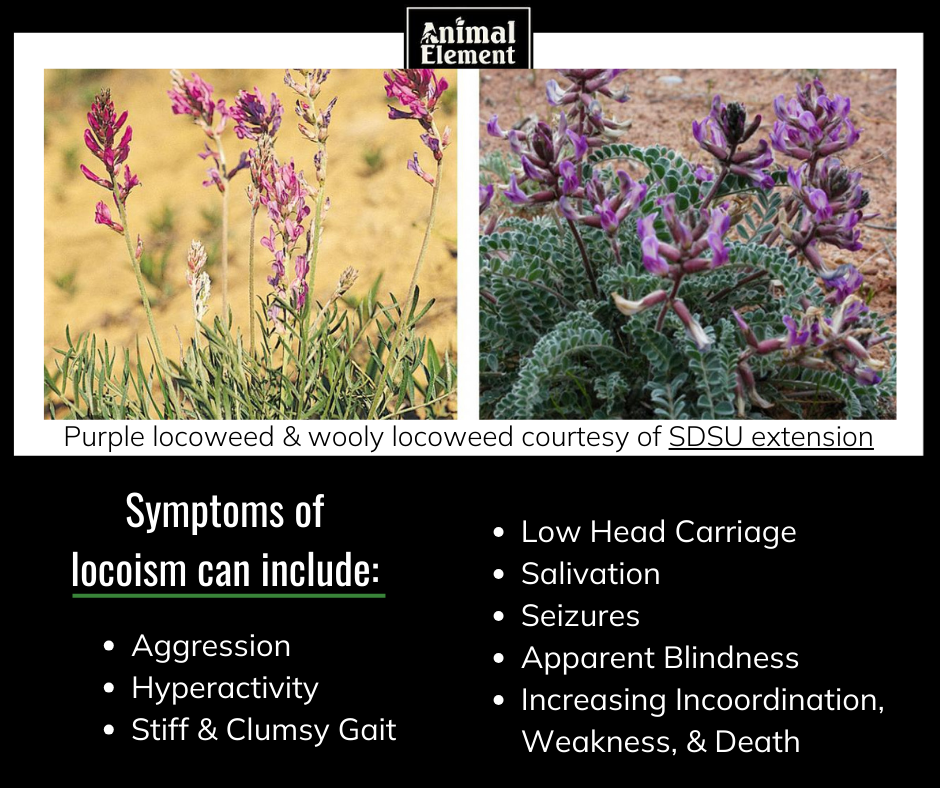

1. Locoweed

This is probably the most well-known toxic plant among horse owners, especially ones living in western states. And for a good reason- locoweed is the number one cause of livestock losses from poisonous plants in the United States. [1] The name locoweed is used to identify any plant that produces a harmful alkaloid called swainsonine, though there are 2 genera in North America (Astragalus and Oxytropis) and numerous species under each genus. [2] Locoweed is generally associated with the genus Astragalus, and crazyweed with the Oxytropis genus, although most people use them interchangeably. Because they both contain swainsonine and have the same symptoms and health risks, we will use locoweed to cover both Astragalus and Oxytropis in this article.

Locoweeds are prolific throughout Western North America, from the North Central plains to the Rocky Mountains, and the Southwestern deserts. They bloom in a variety of colors and leaf shapes, and there are a few “wooly” varieties. (Check out this article from South Dakota State University for differences in the plant species.) They bloom in early spring, usually before other safe grasses, and have extremely hardy seeds that can lie dormant for years until favorable conditions arise. Locoweeds are usually abundant during wet years and die off or lay dormant during dry years. [3]

Unfortunately, locoweeds are semi-palatable and some animals have been known to seek them out, and even get addicted after tasting it. Swainsonine poisoning or “locoism” can take days or weeks to take effect, but targets the central nervous system.

This can look like:

- Aggression

- Hyperactivity

- Stiff and clumsy gait

- Low head carriage

- Salivation

- Seizures

- Apparent blindness

- Increasing incoordination, weakness, and death [4]

It’s extremely important to keep horses and livestock out of the pastures or off rangelands contaminated with locoweed, especially in the spring and fall. Once safer, more palatable forage has grown and the locoweeds have died off, horses and livestock are safe to return. [5] If moving pastures is not an option, make sure to have other forage, minerals, and grains available to keep your horse from wanting or needing to taste test the locoweed.

Signs of swainsonine poisoning usually don’t happen until a large amount of locoweed has been consumed. According to Horse Side Vet Guide, “Once horses show signs of poisoning, the prognosis is poor for return to function. Once affected, horses are also more susceptible to poisoning in the future…

There is no treatment for toxicity once it takes place, other than removing access to the plants. Usually, severely affected horses never fully recover.” [6]

2. Fiddleneck

Amsinckia, commonly known as fiddleneck or rancher’s fireweed, is an annual weed that grows at low altitudes in the Western US and Canada (and parts of South America). The top of the plant curls under, much like the neck of a fiddle. [7] Several species are native to the US, and all are covered with skin-irritating hairs and contain pyrrolizidine alkaloids that will cause liver failure after extended exposure. Clinical symptoms can take months after ingestion to appear, and by then liver damage may have already occurred.

Symptoms of poisoning from fiddlenecks are:

- Appetite Loss

- Colic

- Jaundice

- Behavioral Changes (like depression, aimlessly wandering, head pressing etc.)

- Frequent Yawning

- Photosensitivity

- Loss Of Condition and weight loss

- Diarrhea

- Incoordination and awkward gait [8]

Because of the sticky, irritating hairs covering the plant, a healthy horse does not usually consume fiddlenecks intentionally. The danger is when there isn’t proper forage for the horse to graze on, or if dried fiddlenecks (or their seeds) make it into baled hay.

If you spot a few plants, you can pull them manually while wearing gloves. If the field is densely populated, it’s best to mow them down before seed production. Spraying herbicides isn’t effective as the hairs prevent the chemicals from absorbing into the plant.

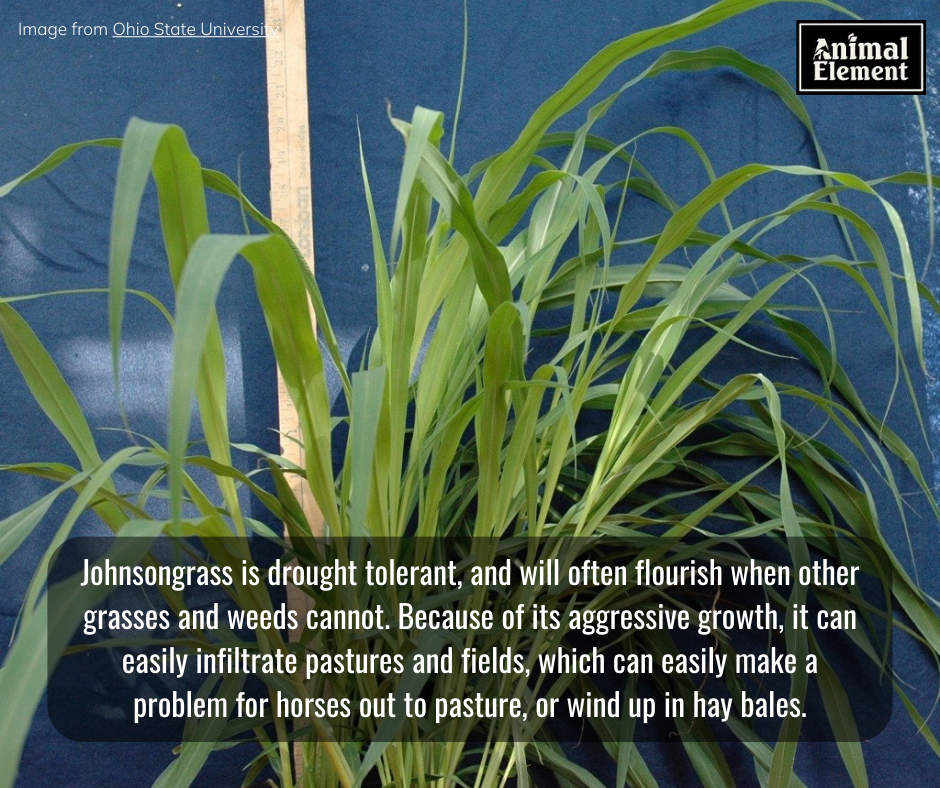

3. Johnsongrass

Johnsongrass is part of the sorghum family and was brought over to the United States from the Mediterranean region in the 1800s. It is found in all 50 states except for Minnesota and is considered a noxious weed in 19 states. [9] It can be an efficient, cheap, and soil-friendly forage for most livestock, except horses.

Johnsongrass is drought tolerant, and will often flourish when other grasses and weeds cannot. Because of its aggressive growth, it can easily infiltrate pastures and fields, which can make it a problem for horses out to pasture, or can wind up in hay bales. If a horse is continuously grazing on johnsongrass (or other sorghums) for weeks or months, symptoms of neuropathy (nerve damage) will appear. It can also cause fetal damage or death if a pregnant mare is ingesting it. [10]

Symptoms of sorghum poisoning can look like:

- Ataxia

- Loss of bladder control

- Eventual paralysis of tail and hind legs

Why horses react to sorghums in this way is unclear, but it’s thought to have something to do with inflammation of the bladder and kidneys, and nerves to the spinal cord. It is unclear exactly how much johnsongrass has to be ingested until clinical signs of toxicity appear, but horses have to be exposed at high amounts for weeks or months. [11]

Monitor your pastures, mow suspected johnsongrass down in the spring before seeds can form, and inspect your hay to ensure it is proper forage for a horse.

4. Milkweed

Milkweed, of the Asclepias genus, is a fairly widespread native species of the United States and parts of Canada and is a common plant in butterfly gardens. They grow wild in a range of soils, usually in disturbed areas like along roadsides, ditches, and fence lines. [12] There are several different species of milkweed, but all have thick, milky sap, tall woody stems, and spiky seed pods that contain numerous seeds.

The most common milkweeds contain cardiac glycosides that effect the neurological, cardiovascular, and digestive systems. [13] Other types of milkweed, like the horsetail milkweed, that have whorled leaves contain a neurotoxin that will cause violent seizures. Both types of toxins only require a small amount to be ingested, about 0.1-0.5% of the horse’s body weight, and can lead to death within 24 hours. [14]

Symptoms of poisoning from both the cardiac glycosides and neurotoxin include:

- Depression

- Dilated Pupils

- Spasms

- Weakness

- Colic

- Irregular Heart Rate

- Uncoordinated Gait

- Labored Breathing

- High Body Temperature

- Convulsions

- Coma [15]

Because of the unpalatable sap, horses do not generally graze on milkweeds intentionally. Because these plants grow alongside fences, ditches, and in agricultural fields, they can end up baled along with other safe hays. Unfortunately, the toxin’s potency is not lessened when dried, so a horse could unknowingly eat a lethal dose of milkweed with their hay. Some species have thick enough stems and big enough leaves that horses can pick them out of the hay, or eat around them, but it’s still a good idea to inspect your hay closely if you don’t know what all is growing in the field where it was cut.

Avoid Dangerous Weeds with Proper Management

Undernourished horses are the most susceptible to poisoning by dangerous weeds. If their pasture is overgrazed and there is nothing else to eat, they will munch on whatever they can find…safe or not. The majority of toxic plants are unappealing to horses, and after a potential test nibble, they will avoid those plants. The most important step is to make sure that your pasture is properly sized and managed correctly, and offer abundant SAFE forage to eliminate any occasional snacking on some poisonous plants. Remember- a horse’s stomach always has to have something in it. They need to be eating small “meals” throughout the entire day. Walk your fence lines frequently and take note of what’s growing there, removing anything unsafe. Many common trees, shrubs, and vines not covered in this article are also toxic to horses.

If at all possible, know where your hay is grown and cut, to avoid any dangerous weeds getting mixed into the bales. Buy from reputable farmers that you know manage their fields well. Inspect the bales as well as you can before buying or feeding and always pay attention to even the smallest changes in your horse’s health and behavior.

All content is intended for informational purposes only. Proudly written for Animal Element by the team at FaithHanan.com

Symptoms vary from plant to plant, but usually, the first signs something is wrong are changes in appetite and behavior, depression, and often colic.

Again, this varies depending on which plant they are munching on. Clinical symptoms for some dangerous weeds may take weeks to months to appear, while other plants can cause damage IMMEDIATELY. It’s safe to say that any amount of toxic weeds consumed is too much.

Usually, horses will not graze on plants that are toxic to them IF they are sufficiently nourished. Providing appropriate forage sources, making sure to not over-graze pastures, and practicing good weed management are ways to avoid potential disasters.

Contact your local extension office to get information about which plants in your region could cause harm to your horses and livestock.

Resources for Dangerous Weeds:

- Ehlert, Krista. “Poisonous Plants on Rangeland: Locoweed and Crazyweed.” 24 October 2022. South Dakota State University Extension Office. https://extension.sdstate.edu/poisonous-plants-rangelands-locoweed-and-crazyweed

- “Locoweed.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Locoweed

- “Locoweed Information Guide.” University of Arizona Cooperative Extension. https://extension.arizona.edu/locoweed-information-guide

- “Locoweed Information Guide.” University of Arizona Cooperative Extension. https://extension.arizona.edu/locoweed-information-guide

- “Locoweed Information Guide.” University of Arizona Cooperative Extension. https://extension.arizona.edu/locoweed-information-guide

- Thal, Doug. “Locoweed Toxicity.” Horse Side Vet Guide Knowledge Database. https://horsesidevetguide.com/drv/Diagnosis/461/locoweed-toxicity/

- “Armsinckia.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amsinckia

- “Fiddleneck.” HorseDVM. https://horsedvm.com/poisonous/fiddlenecks#google_vignette

- Rocateli, Alex. “Johnsongrass in Pastures: Weed or Forage?” April 2017. Oklahoma State University Extension. https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/johnsongrass-in-pastures-weed-or-forage.html

- Gaskill, Cynthia. “Toxin Topic: Johnsongrass Poisoning in Horses.” November 2010. University of Kentucky Ag Equine Programs. https://equine.ca.uky.edu/news-story/toxin-topic-johnsongrass-poisoning-horses

- Gaskill, Cynthia. “Toxin Topic: Johnsongrass Poisoning in Horses.” November 2010. University of Kentucky Ag Equine Programs. https://equine.ca.uky.edu/news-story/toxin-topic-johnsongrass-poisoning-horses

- Turner, Jason. “Milkweed Poisoning of Horses.” New Mexico State University College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences. https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_b/B709/index.html

- “Cardiac Glycoside.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cardiac_glycoside

- Turner, Jason. “Milkweed Poisoning of Horses.” New Mexico State University College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences. https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_b/B709/index.html

- “Common Milkweed.” HorseDVM. https://horsedvm.com/poisonous/milkweed#google_vignette